Going Dark- plague, quarantine, and the resilience of theatre

- Grace Davidson-Lynch

- Apr 9, 2020

- 7 min read

Scrolling endlessly through Instagram, I found a video published last month by Belvoir Theatre. In it, artistic director Eamon Flack speaks about the closure of the theatre, and explains the concept of going dark. When a theatre is not in use it is common for a light mounted on a stand, called a ghost light, to be left on in the auditorium. This is a safety measure to illuminate the space, but as with all theatre traditions, it has come to have profound meaning. As Flack says “…we are going to leave a ghost light burning because the work of this theatre is far from over.” Belvoir is not alone- theatres all over the world are going dark, single lamps filling their spaces with some light until this is all over. It is a light at the end of the tunnel, and it is a promise to pick up where they left off.

Flack’s message is a beautiful display of resilience in the face of a crisis that is unprecedented in the history of the company. And as I sat, stuck in my little flat with no end in sight, I began to think about history. As I slowly go mad, I thought it best to dedicate some time to understanding how we got here. This is not the first time in history that the work of theatres and cinemas has been disrupted by disease. We stand to learn a lot- as artists and as audiences- from the impact of past pandemics.

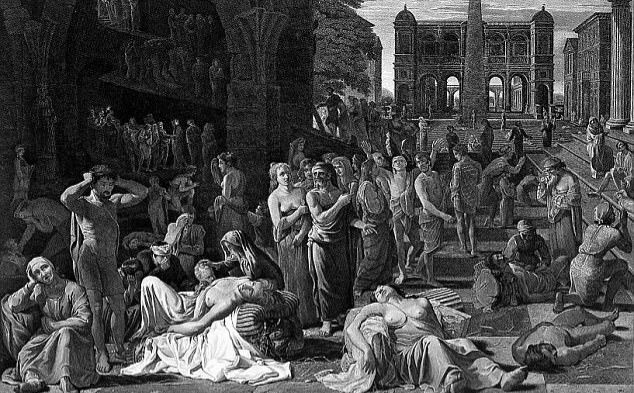

Plague and theatre have a connection that is as old as Western theatre itself. And this relationship reveals not only how people in different times reacted to disease and death, but how theatre responded to those reactions. Several of the most significant Ancient Greek dramas that have survived were written around 420 BCE, when plague (possibly typhoid) emerged in Athens and wreaked havoc for several years. It is wonderfully poetic to suppose that the Greek Tragedians provided their audiences with moving and grotesque portraits of disease that resonated with them in a time of grief. As Mitchell-Boyask suggests, the theatre operated as something of a political healer in the aftermath of the plague. But in reality, the audience response was probably more complicated.

Mitchell-Boyask analyses the language used by Sophocles and other playwrights to determine what social power the plague had come to represent in Athens at the time. In Ancient Greek, the word loimos is used to refer to plague, with the word nosos used to describe diseases more generally. Despite evidence that several plays were written in the aftermath of the Athenian plague, few of them actually use the word loimos. Oedipus Rex only contains one usage of the word, said by the Priest as he tells Oedipus of the effects of plague on the city of Thebes. This retirement of the word loimos, but not nosos, implies a new taboo- as Mitchell-Boyask argues, “…this word’s disappearance from Athenian literature… suggests that Sophocles is signalling that loimos is an ‘inauspicious word’.” And even with this careful selection of language, the play placed second at that year's festival of Dionysus. Mitchell-Boyask finishes their article with this notion- “…poets could heal, but only so much, perhaps because their patient became unwilling to listen (2009, pg. 375).” There is a good chance that audiences on the other side of the current crisis won’t respond well to plague theatre. If references to the plague were enough to move Oedipus Rex down to second place, we can only wonder how the playwrights and performers of the future will fair.

The concept of quarantine seems new- it is certainly new for those of us currently practising it. But artists have been forced into quarantine many times over centuries of disease control. I’ve seen this sentiment emerging online in one particular form- if Shakespeare wrote King Lear while in quarantine, image what you can get done! This is arguably an unhelpful slogan to spout, as artists everywhere suffer the economic consequences of not being allowed to continue working. I truly hope someone out there is inspired to create a masterpiece during this crisis, but comparisons to the Bard’s ability to keep creative in the face of mass death is not a resilience that is universally applicable. What I personally find more interesting is how the Black Death specifically impacted the running of Shakespeare’s theatre.

It seems that Shakespearean theatres had more frameworks in place for dealing with constant closures and disruptions brought on by plague. Firstly, the standard by which theatres were closed due to plague was drastically different from those we are practicing today. Our theatres and venues closed after a ban of 50 people or more indoors as a precautionary measure- one record from the 17th century states that theatres close if plague deaths were recorded at being above 30 or 40 in a week. Diversifying income streams would have been next-to impossible for the plague-affected writers of the 17th century. In his book Shakespeare on Toast, Ben Crystal highlights the cost of manuscript printing at that time as a reason why so few plays could be published. To compound this, as plays were rarely restaged and the demand for new plays was very high, playwrights “…were left with the option of either trying to print unused manuscripts of their own, or writing poetry (2012, pg.21).” But there is evidence to suggest that Shakespeare’s theatre troupe were provided funds and allowed to practise at numerous points in their history as their place of business remained closed. Financial records document miscellaneous payments during plague closures, including one in 1609 of £40 (around £10,000 today) to the King’s Servants, given as “…his Majesty's reward for their private practice in the time of infection that thereby they might be enabled to perform their service before his Majesty in Christmas holidays (Barroll, 2005, pg. 159).” It seems that at least King James may have been able to enjoy his personal theatre troupe’s creative efforts. One can only hope that His Majesty watched from at least 1.5 metres away from the stage.

What these details can teach us it that Shakespearean theatre was constantly facing the threat of plague, and so was more adept at handling widespread pandemics. That Shakespeare wrote King Lear and other plays while in self-isolation is less significant when you consider how often his work could have been impacted by theatre closures, and how quickly he was producing new work regardless of quarantine. For the playwrights of today, this crisis is unprecedented and terrifying. For Shakespeare, it was fairly common and he often worked around it. King Lear was not written because Shakespeare had already watched everything on Netflix.

But we don’t live in ancient, unclean times- bubonic plague and typhoid are hardly common concerns of the average theatregoer. The 2020 coronavirus has been compared frequently to the Spanish flu outbreak in 1918, the most recent widespread pandemic to affect millions of people. This plague can demonstrate how audiences will be impacted by the virus moving forward. Richard Koszarski chronicled how the spread of influenza began to affect movie theatres, and what their eventual reopening looked like. Fear of the pandemic was not dissolved overnight- as Koszarski describes, “…when theatres did reopen business was not always as good as expected, especially if a resurgence of the epidemic kept frightened audiences away (2005, pg. 467).” However, it was not always fear of death which prevented theatres from returning to economic normality after the flu had passed. One newspaper article included in Koszarski research, dated 16th November 1918, notes that-

“…every manager reported large audiences with a prospect of one of the best seasons in years. Then the weather man stepped in with some of the warmest October days known in years, and after the depression of the epidemic, people flooded into the public parks and out-of-door places in preference to attending the theatres (pg. 476).”

I came across this fact, and it genuinely restored some hope in me. This is a charming sort of problem, and one that is less horrific than frightened patrons too scared to attend the theatre. The people wanted to spend time in the sun, rather than watching movies. That’s a scenario a lot of people can relate to right now, and one that I feel is likely to play out when this is all over. The film industry obviously recovered after the pandemic, but the human need to feel safe and enjoy nice weather were ultimately important factors in that recovery.

As I write this it is pouring with rain outside. It’s weather that is suitably belligerent. Stay inside, stay inside, it’s pouring with rain- we understand. I do not begrudge the decisions made by theatre operators and the government of this country. We need to keep audiences safe, first and foremost. But theatre is powered by an urge to be seen and gather. Performers and writers want to share, and audiences want to be shared with. It’s the reason why theatre has held the attentions of audiences spoilt for choice in the age of new media. Why leave home and go to a theatre to see a live performance? Can’t you get the same feelings from the art you can consume at home?

Of course not.

Going dark is a logical step in preventing illness and death in our communities. But going dark collides with the emotional needs of communities impacted by social and economic devastation. Every section of society is feeling this. But I am hoping this crisis- and this little history lesson I've provided here- will teach us that theatre always bounces back. It has also served as a profound reminder of why theatre matters. It has taught me a great deal about the power of being present. Present with my friends and family. Present with my students and other artists. And present with the art I love, the art that inspires and motivates me.

John Steinbeck is often quoted as saying that the theatre is the only institution in the world that has been dying for 4,000 years and never been defeated. Wars, financial disasters, political upheaval, and the newest challenges of a world less present than ever haven’t defeated it yet. Even plagues haven’t defeated it. This crisis will pass, and we will return to work.

And as always, the theatre will be waiting for us.

References-

Mitchell-Boyask, R 2009, ‘The art of medicine plague and theatre in ancient Athens’, Lancet, vol. 373, no. 9661, pp. 374-375.

Koszarski, R 2005, ‘"Moving Picture World" Reports on Pandemic Influenza, 1918-19, Film History, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 466-485.

Crystal, B 2012, Shakespeare on Toast, Icon Books, London.

Bank of England, Inflation calculator, Bank of England, viewed 2 April 2020, <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator>.

Barroll, L 2005, ‘Shakespeare and the second Blackfriars Theater’, Shakespeare Studies, vol. 33, pp. 156-170.

Belvoir 2020, Important Information about Belvoir, 26 May, Belvoir, viewed April 1 2020, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eZcYSdxZoA8>.

Images-

Ghost light in Auditorium Theater © Matthew Gilson

Poussin, N 2016, The Plague at Athens, image, Ancient History Encyclopedia, viewed 2 April 2020, <https://www.ancient.eu/image/5521/the-plague-at-athens/>.

Guarino, B 2018, The classic explanation for the Black Death plague is wrong, scientists say, 17 January, The Washington Post, viewed April 8 2020, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2018/01/16/the-classic-explanation-for-the-black-death-plague-is-wrong-scientists-say/>.

Thompson, D 2018, Could the deadly 1918 flu pandemic happen again?, 9 February, The Chicago Tribune, viewed April 8 2020,

Comments